|

When standing in the open filed, surrounded by a few shrubs and shallow holes, it is hard to imagine the beehive of activity described as follows in the journal of E. O. Stratton:

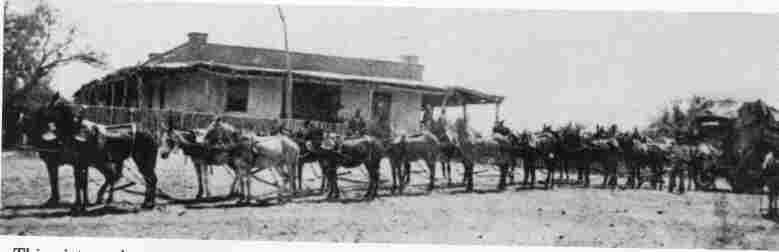

"Though small, Maricopa Wells was a busy place. The stages passing twice a day, one eastbound and one westbound, changed animals and fed their passengers here. When troops were discharged - and this was often - the stages were full both ways. At other times there was a predominance of passengers from the west. Not only were many Californians coming into the country, but there also were the Easterners who had gone by train or around the Horn to San Francisco, then came down the coast to San Diego and into Arizona by stage. Then, too, Maricopa Wells was the division point for Phoenix, Fort McDowell on the Verde, and other places to the north. The camping ground outside the enclosure was also a busy place. Great freight trains of three or four wagons and eight to twenty mules were often camped there; and detachments of soldiers - from a few scouts to one or more companies - might turn in for the night. Soldiers scouting through the immediate country usually made Maricopa Wells their supply station; and all westbound traffic, whether or not they camped, had to load up with enough water to last across the desert from Maricopa to Gila Bend, a distance of forty-five miles which meant at least one night's camp."

Arizona's first Mini-Mall. One of the few pictures of the old station. This was a major post on trail to California when Phoenix was still Pumkinville.

By 1870, when Maricopa Wells station was purchased by well-known pioneers James A Moore and Larkin Carr, it had become what may be called Arizona's first mini-mall, with a general store, saloon, staff living quarters, an office, a blacksmith shop, stables, and a hotel, all in one long "U" shaped building surrounding a two acre square enclosed by a high abode wall on the open end. The Wells, famous for its hospitality and fine kitchen fair, was probably the only place between Texas and California where a good hot meal was served to the traveller, often with live music provided by Moore's twin daughters.

By the middle of the 19th century, traffic on the trail was intense. In the three years following the discovery of gold in California, more than 60,000 people crossed the ferry at Yuma, almost all of these passing through Maricopa. The diary of George Evans, a Forty-Niner, mentions at least seven companies camped at or passing through the Pima villages in the two days he was there.

Under different circumstances, Maricopa Wells could have become Phoenix. For 15-20 years it was the only Anglo (or American) establishment in what is now the Metropolitan Phoenix area. It wasn't until the mid 1860s that Mormons and other pioneers began moving into the Area. It wasn't until 1868 that Jack Swilling dug is canal and founded the city that could have been called Swilling's Mill, Stonewall, Pumpkinville, Hellinwg Mill, Salinas, or Mill City but ended up as East Phoenix and then finally Phoenix. I would be really unhappy if I had been born in Pumpkinville!

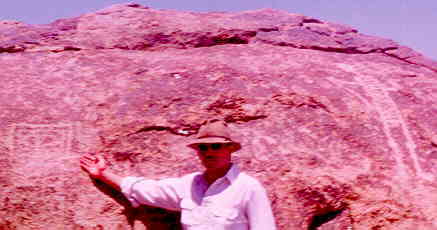

Montezuma's Head at the southern point of the Estrellas, from the old trail going west

There is an uncertain link between the Sierra Estrellas and the Legend of Montezuma, whose name is given to three points on the mountains. I remember as a boy standing in the track of the Butterfield stage trail and my Dad pointing out the profile of Montezuma's Head at the southeast end of the mountain. The second (?) highest peak in the range is also called by the name of the old Aztec emperor, although he assumes mystical or god-like attributes in many of the legends, particularly those circulating a century ago. The mountain crest north of that peak up to Butterfly peak is know as the Montezuma Sleeping, because it supposedly portrays a the profile of a sleeping giant. Montezuma's Head (?) was clearly recognizable, even as a boy I had quite a bit of trouble coming up with the sleeping man figure, and nothing has changed.

Although some experts may disagree, the Estrellas do not seem to possess any particular deep religious or mystical significance to the Indians. Anybody who visits this range will surely leave it with a reverence for their unyielding roughness and respect for the dangers. Even the legends of Montezuma seem to be less the product of Indian folklore then result of the 19th century American fantasy, based upon original misunderstanding of Jesuits priests, who were unwilling to give credit where credit was due, with regard to the building ability and architectural achievements of the ancient natives in the Southwest.

One of the few other peaks in the Estrellas that has been honored with a name is the Beardache Mountain at the northern end [Spier, p. 252] From this peak Maricopa and Yuman warriors would trade insults prior to a skirmish.

Paul and John at the ranch in Maricopa, about 1950. Traffic was better then... Notice Estrellas in background.

So it was with somewhat low expectations that I decided to revisit the southern regions of the Sierra Estrella mountains - my family's special camping place in the 1950's. Our acquaintance with this range goes back to the time of my grandfather, who came to Arizona in 1899 on his way to Montana or Dakotas. Fortunately he stayed and homesteaded in the Maricopa area, about 35 miles south of Phoenix, where my father was raised.

At that time signs of man were mostly limited to the winding trails, numerous petroglyphs (we called them hieroglyphics), broken pottery and an occasional arrowhead. We would also frequently run across piles of rock marking mining claims with the notices placed inside tobacco tins. I remember on one occasion spending a couple of hours with my father looking for an old massacre site near Montezuma's Head where Indians had settled scores with an unlucky wagon train. A semicircle of mounds that marked the final resting place of a few forgotten drivers, which had been visible when he was young, was no longer to be found. I had never come accross any reference to this locale until stumbling accross an unsigned report in the Maricopa Public Library refering to an interview in which pioneer Dallas Smith mentions having seen this site. he also mentions a treasure. Oh well, why not? (It was the stuff of which good memories are made, and was great fun for a young boy.)

Leaving Tempe one crosses a somewhat mysterious line marked only on the older maps but not so evident on newer ones. From a point at the confluence of the Gila and Salt Rivers a Meridian line extends north and south and a Base line runs east to west All land in Arizona is measured in six mile squares from the intersection of these lines. With the post World War II population explosion in Arizona the Gila and Salt River Base Line found on older maps in now simply Baseline Road on the metropolitan Phoenix maps.

After passing Pima Butte, we would turn west and follow the road to St. John's Mission, a Catholic boarding school for indian children, founded in xxxxx and deactivated in xxxxx. Form there our usual course was to follow the old gasoline road straight to near to a point known as Montezuma's Head. Here, among a jumble of rocks often as big as houses, are the famous petroglyphs.

Unfortunately, time and people have not been good to the petroglyphs. Nature - in the form of scorching days and cool nights, rain, wind and sand storms - is slowly obliviating the ancient artist's work. The worst enemy has been modern man, especially those possessing spray paint. As John Annerico says, if you want to see the petroglyphs, go now because if they continue to be destroyed and deteriorate at the present rate, this will be the last generation to enjoy them. The grinding holes (bedrock morters) are only there because nobody has yet figured out to put ten or so tons of solid rock into the back of a pickup.

Reavis, The Baron of Arizona

Among the hundreds of figures is one that could easily be mistaken for just another piece native American rock art, but it has a different story to tell. It is the initial marker point for the Peralta Grant. In fact, a photograph showing Dona Maria ... standing in front of a well decorated rock at zero ground is the earliest picture that I've seen of the petroglyphs. This Peralta Grant was a bogus claim based upon counterfeit documents that, if successful, would have given a certain Revis ownership a rectangular chunk of land 50 to the north and 50 miles to the south and 250 miles to the east of the marker, all the way into New Mexico. The claim was being examined by the U.S. government and declared fraudulent, but not before Revis had caused quite a bit of excitement and managed to pocket up a couple of hundred thousand dollars in xxxxx, land sales and stock. It is interesting that the proof documents, dating from 1760, specifically name the Sierra Estrellas by name, but I suppose there was a certain logic to his madness - why bother to prepare, alter and replace hundred of documents to steal a piece of land if you cannot prove it's localization.

The Baroness at the Peralta marker, Southern end of the Estrellas, in the 1880s

Indiana Mike and the same Marker, over 100 years later.

Dad in front of Hotel, about 1930. Notice water tank.

Today things are very different. No longer does water glisten in the riverbed or green trees and marshes do not mark the path of the Gila and Santa Cruz. The land is still being cultivated, however in a manner Antonio Azul would never recognize. To the southeast, among large squared fields is Maricopa, a town established in 1880 on the railroad line and for many years a transfer point for all passengers going to Phoenix and northern Arizona. And so Maricopa, located seven miles south of the old stage stop, took away from the Wells not only its customers, but also its name. However the new town, after a few years of growth, acquired a certain immunity to progress and growth that it may finally overcome with the construction of a new highway to Phoenix. (Talk about Maricopa land scam )

For more information on the Sierra Estrellas check out these pages here:

The Story of the Estrellas

I wonder if anybody, looking at the marker among hundreds of petrographs around it, knows what it is?Montezuma, Forty mile Desert

Climbing the mountain above the petroglyphs will put you on top of Montezuma's Head. According to Petroglyphs of the Southern Sierra Estrellas, there is an ancient trail leading up to a tinaja, a natural pool (?), and a rock shelter near the crest of the peak. Standing there, where probably many a warrior had stood as a look-outs, you can easily imagine the panorama as it was 140 years ago. You would see the whole of the Maricopa plain, cut by the and Gila River, and in very wet seasons, the Santa Cruz. Below you to the east would be eight to ten Pima villages, near the Gila mostly, surrounded by fertile green fields. The Maricopa villages, to your right and father north, would probably not be visile. You could easily trace the track of the Gila Trail - a dusty brownish scar running thought the shrubs and fields as it crossed the plain below a small rounded mountain and angled away from the green tree lined river across a grassy field where morning fires would reveal that American travellers were preparing breakfast at a place yet to be called Maricopa Wells. From there, your eye could easily follow the trail as it runs in a southwestern direction along the arroyos in a fairly straight path, slowly gaining elevation, until it meets the mountain directly below your feet. Here you would probably see travellers stop to check their equipment and supplies - mainly water flasks - and maybe appreciating the art gallery - before rounding the mountain and heading directly west across the Forty Mile Desert, where they would rejoin the Gila. If you were a Pima, having lived in the same spot for hundreds of years, you might wonder at the wondering ways of the Americanos, but this would be a minor consideration, as your main thought would be spotting and identify any suspicious movement that might mean approaching raiding parties from the tribes to the west or even from the south.Rivers, flora and fauna of the region

Man has brought great changes to the habitat. The sandy washes and dry riverbottoms of today present us with a very different picture of what the region was like up to as recently as 150 years ago. Imagine the Salt and Gila Rivers flowing freely, joined by waters from the Santa Cruz, Agua Fria and Hassayampa created a situation/vision that would certainly seam very strange to us today, freeflowing streams bordered by lush vegetation with marshes, lagoons and islands, populated/inhabited by a wide variety of waterfowl and aquatic life and animals. the disappearance of the Gila - San Pedro waterways, which provided several hundred miles of dependable shelter, must have been a major disruption to migrating birdlife.

Maricopa Wells and the stage route

Old Charts of Region

The Old Spanish Mine

Maps of the Estrella Mountains

The Patio - the most historic area of Estrellas